The evolution of giant mammals following dinosaur extinction

Release Date 26 November 2010

Researchers have demonstrated that the extinction of dinosaurs 65 million years ago paved the way for mammals to become a thousand times bigger than they had been before.

The study, undertaken by academics around the world, including those from the University of Reading, is the first to quantitatively explore the patterns of body size in large mammals after the demise of the dinosaurs.

Professor Richard Sibly, a co-author on the project, from the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Reading, said: "The dinosaurs were wiped out by a giant asteroid and their extinction left room for the evolution of the large mammals that replaced them. The dinosaurs dominated the Earth and killed everything that got in their way; once they became extinct the mammals were able to thrive."

The research, published in Science today, was led by Felisa Smith from the University of New Mexico and brought together an international team of paleontologists, evolutionary biologists, and macroecologists.

The goal of the research was to see how fast mammals evolved and how big they grew. The paleontologists in the team estimated body size from fossil teeth, which are commonly preserved. Scientists have long known that size profoundly influences biology, from reproduction to extinction.

Professor Richard Sibly, said: "Our data are unique, both in terms of the amount of data and because we compared mammals on all continents since the extinction of the dinosaurs."

Researchers collected data on the maximum size for major groups of land mammals on each continent, including Perissodactyla, odd-toed ungulates such as horses and rhinos; Proboscidea, which includes elephants, mammoth and mastodon; Xenarthra, anteaters, tree sloths, and armadillos; as well as a number of other extinct groups.

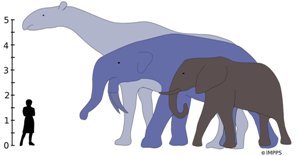

The study found that mammals grew from a size of about 10 kilograms when they were sharing the Earth with dinosaurs to a maximum of 17 tons afterwards. The pattern of increase in the size of mammals was surprisingly consistent across space, time and trophic groups and lineages. The maximum size of mammals began to increase sharply about 65 million years ago, peaking in the Oligocene Epoch (about 34 million years ago) in Eurasia, and again in the Miocene Epoch (about 10 million years ago) in Eurasia and Africa.

The largest mammal that ever walked the earth is the Indricotherium transouralicum, a hornless rhinoceros-like herbivore that weighed approximately 17 tons and stood about 18ft high at the shoulder that lived in Eurasia almost 34 million years ago.

Professor Sibly said: "The results are striking. We think that global temperature and terrestrial land area set constraints on the upper limit of mammal body size, with larger mammals evolving when the earth was cooler and the land area greater. The fact that we find such similarity in the trajectory of mammalian body size evolution among different continents suggests that mammals were responding to similar ecological constraints despite differences in geology."

The study was funded by a US National Science Foundation Research Coordination Network grant.

ENDS

For more information please contact Rona Cheeseman, press officer, on 0118 378 7388 or email r.cheeseman@reading.ac.uk

Notes to editors

Professor Richard Sibly is interested in finding general ecological laws that can be used to compare animals of different sizes.

His colleagues in this project include Felisa Smith, Alison Boyer, James Brown, Daniel Costa, Tamar Dayan, Morgan Ernest, Alistair Evans, Mikael Fortelius, John Gittleman, Marcus Hamilton, Larisa Harding, Kari Lintulaakso, Kathleen Lyons, Christy McCain, Jordan Okie, Juha J. Saarinen, Patrick Stephens, Jessica Theodor and Mark Uhen.