The impossible staircase in our heads: How we visualise the world

Release Date 22 March 2012

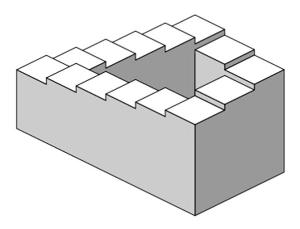

Our interpretation of the world around us may have more in common with the impossible staircase illusion than it does the real world, according to research from the University of Reading.

The study, funded by the Wellcome Trust and published in the open access journal PLoS ONE, suggests that we do not hold a three-dimensional representation of our surroundings in our heads, as was previously thought.

Artists such as Escher have often exploited paradoxes that emerge when a 3D scene is depicted by means of a flat, two-dimensional picture. In his famous picture 'Waterfall', for example, it is impossible to tell whether the start of the waterfall is above or below its base. Paradoxes like this can be generated in a drawing, but it is not possible to create such a 3D structure. The illusion is possible because drawings of 3D scenes are inherently ambiguous, so there is no one-to-one relationship between the picture and 3D locations in space.

Most theories of 3D vision and how we represent space in our visual system assume that we generate a one-to-one 3D model of space in our brains, where each point in real space maps to a unique point in our model. However, there is an on-going debate about whether this is really the case.

To test this idea, researchers at the University of Reading placed participants wearing a virtual reality headset in a virtual room in which they had to judge which of two objects was the nearest.

On some occasions, the size of the room was increased four-fold - previous research by the team showed that participants fail to notice this expansion. In this new study, the researchers found that people's judgement of the relative depth of objects depended on the order in which the objects were compared. Although the results are readily explained in relation to the expansion of the room, the participants had no idea that the room changed at any stage during the experiment. It is the properties of this stable perception that the experiment tested.

Dr Andrew Glennerster, from the School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences, who led the study, explains: "In the impossible staircase illusion, you cannot tell whether the back corner is higher or lower than the front one as it depends which route you take to get there. The same is true, we find, in our task. This means that our own internal representations of space must be rather like Escher's paradoxes, with no one-to-one relationship to real space.

"Even when the size of the room increases four-fold, people think they are in a stable room throughout the experiment. Their interpretation of the room does not update itself when the room itself changes. Does it make sense for their representation of the room to have 3D coordinates, as a proper staircase would? No - there is no way to write down the coordinates of the objects that could explain the judgements people made. Visual space - the internal representation - is much more like the paradoxical staircase than a physically-realisable model."

Ends

For more details contact Pete Castle, University of Reading press office, on 0118 378 7391 or p.castle@reading.ac.uk, or Craig Brierley, Senior Media Officer, The Wellcome Trust on 020 7611 7329 or c.brierley@wellcome.ac.uk

Notes for editors

Svarverud, E et al. ‘A Demonstration of ‘Broken' Visual Space'. PLoS One; 22 Mar 2012

The University of Reading is ranked among the top 1% of universities in the world (THE World University Rankings 2011-12) and is among the top 20 universities in the UK for research funding.

The School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences at the University of Reading has a long-standing reputation for excellence in experimental psychology, perception, learning, memory and skilled performance. Research strength includes work in the field of developmental psychology, neuroscience, ageing, virtual reality and multimedia interactions.

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. It supports the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. The Trust's breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. It is independent of both political and commercial interests. www.wellcome.ac.uk