Climate change pledges will avoid significant effects of global warming, but could go further

Release Date 11 December 2015

Climate pledges could save several million people from being affected by flooding rivers, heatwaves and water shortages in the twenty first century.

According to new research led by four top climate science institutions, pledges made by 185 countries before the Paris 2015 UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) could significantly reduce the risks to society and ecosystems in many parts of the world.

Although the team of researchers warn there is a high degree of uncertainty around the exact scale of the effects, their new analysis suggests that, compared to a situation where greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, if the pledges are fulfilled, then in 2100:

- 60 million fewer people would be affected by river flooding every year

- 220 million fewer people would be exposed to increased water shortages

- 7.7 billion fewer instances of people experiencing a heatwave

- 1.9 million fewer square kilometres of cropland would become less suitable for farming

- 40 per cent fewer plants and animals species would lose over half of their habitat.

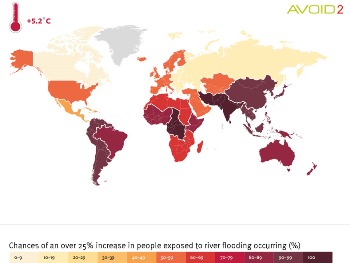

The study projected what a future would look like in 2100 if emissions continue to rise unchecked. It found this scenario could result in an average of 5.2°C global warming - relative to pre-industrial temperatures (1850-1900) - with land warming more than the oceans, and the poles warming more than tropical latitudes. The scientists compared this with a scenario that sees 3°C global warming by 2100, if annual greenhouse gas emissions are capped at 54 billion tonnes globally from 2030 onwards. Today's emissions are just over 50 billion tonnes.

A new set of infographics also highlights the effects that global warming of 5.2°C in 2100 could have on different regions around the world, when contrasted with the effects of 2°C warming. In 2010, the UNFCCC agreed a long-term goal to limit global warming to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, however it is still being discussed at in Paris whether to strengthen this goal keep warming below 1.5°C.

The research was carried out as part of the "AVOIDing dangerous climate change" (AVOID 2) programme led by the UK's Met Office Hadley Centre, alongside the Grantham Institute (Imperial College London), Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research (University of East Anglia), and Walker Institute (University of Reading), in collaboration with a number of other leading climate change and energy research institutes.

Professor Nigel Arnell, AVOID 2 Lead Scientist from the Walker Institute at the University of Reading, said: "The Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) are a start towards reducing greenhouse gas emissions, limiting global warming and avoiding harmful impacts on people. But by going further and achieving the 2°C goal, even greater improvements could be made. Our analysis shows what a difference limiting temperature rise to 2°C could make to people across the globe.

Dr Rachel Warren, AVOID 2 Lead Scientist from the Tyndall Centre at the University of East Anglia, said: "Climate change will reduce the geographic range that plants and animals can inhabit, but limiting global warming to 2°C as opposed to 5.2°C would reduce these effects by more than 60 per cent. By acting to keep climate change below 2°C we can also slow the overall rate of warming, which would buy around three decades of additional time for species to adapt. For society too, this will make adapting to new conditions cheaper and more effective than it otherwise would be."

Mr Ajay Gambhir, AVOID 2 Lead Scientist at the Grantham Institute, Imperial College London, said: "Can we get to 2°C? It is still technically and economically feasible, but it will be challenging to achieve such rapid, wholesale changes to energy systems across the world, particularly if we delay coordinated international action towards this goal."

Professor Jason Lowe, AVOID 2 Chief Scientist, of the Met Office Hadley Centre, said: "The window of opportunity to avoid potentially dangerous impacts is narrowing rapidly as the world uses up the global carbon budget compatible with the 2C goal. If this happens, evidence suggests that the later emissions are reduced, the more we will rely on technologies to artificially remove atmospheric carbon dioxide. One such example uses bioenergy crops to feed power stations that capture and store greenhouse gases, known as BECCS.

"Importantly, this has not yet been proven at commercial scales, and it is not yet clear how much carbon dioxide we can effectively remove. But it would be a less risky strategy to avoid relying on negative emissions technologies, instead taking action sooner to reduce global emissions."

"We need to accept that many scientific uncertainties do remain but they are not a reason for inaction. However, it is also important to retain some flexibility in the process of setting future commitments and the long-term goal so that we can take improving knowledge into account and minimise the risks to people and economies."

Mr Gambhir said: "The AVOID 2 research provides a detailed scientific evidence base towards the scale of the challenge, but also the scale of the global benefits. As well as assessing the feasibility of the 2°C goal, we could now provide a framework for assessing the implications of the even more ambitious 1.5°C goal that is still an option for the Paris agreement."