Solar eclipses and the Middle Ages

Release Date 19 March 2015

Dr Anne Lawrence from the University of Reading's Department of History examines what solar eclipses meant to our ancestors

Looking forward to the solar eclipse? I am and I suspect much of the UK is too. Scientists in particular are chomping at the bit to record this once in a generation event, especially here at Reading where we have organised the National Eclipse Weather Experiment which we can all take part in.

But looking back through the history books excitement wasn't the only emotion being felt leading up to an eclipse. These events had a shadowy effect not just on the weather, but people's lives as well... or so it was believed.

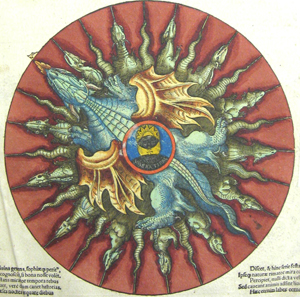

In the 12th century the chronicler John of Worcester wrote: ‘in 1133 a darkness appeared in the sky throughout England. In some places it was only a little dark but in others candles were needed. ... The sun looked like a new moon, though its shape constantly changed. Some said that this was an eclipse of the sun. If so, then the sun was at the Head of the Dragon and the moon at its Tail, or vice versa. ... King Henry left England for Normandy, never to return alive.'

The account mixes astronomical knowledge of eclipses with a fateful link to political turmoil, encapsulated by the image of the great celestial dragon, whose head and tail mark the points on the orbits of the sun and moon at which eclipses can occur. In spring the moon's path crosses that of the sun at the ‘head of the dragon', whilst the autumnal point is the ‘tail'.

The oldest references to the dragon seem to come from Babylonian astronomers. However, there is some confusion as to whether their concept was as scientific as the later one, or whether it referred to a belief that a celestial dragon caused eclipses by swallowing the sun or the moon.

The idea of the celestial dragon as a way of depicting the lunar nodes (the points of intersection of the sun's orbit and the moon's) was taken up by Hindu astrologers and astronomers, who influenced the Arabs. It is referred to by classical astronomers, but seems to have come into medieval Europe via translations of Arabic works on astronomy/astrology.

The significance of eclipses is recorded in the court of Charlemagne, where there was also debate on when they would occur and how accurately they could be predicted. Charlemagne's son, the Emperor Louis, died shortly after witnessing an eclipse, and some writers linked the two together.

In the 9th century the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records eclipses in a way which links them with Viking invasions.

‘879: A band of invaders gathered and established a base at Fulham; and in the same year the sun was eclipsed for one hour of the day.'

In 1140 William of Malmesbury recorded another eclipse. He wrote: ‘There was an eclipse throughout England, and the darkness was so great that people at first thought the world was ending. Afterwards they realised it was an eclipse, went out, and could see the stars in the sky. It was thought and said by many, not untruly, that the king would soon lose his power.'

So when you gaze upwards spare a thought for our ancestors...and the dragon that hides behind the clouds.